Breaking News Emails

Get breaking news alerts and special reports. The news and stories that matter, delivered weekday mornings.

Dec. 8, 2018 / 2:58 PM GMT

By Elizabeth Chuck

Raquel Cruz has a lot of stress in her life. A single mother of three daughters, she is the manager of a small health clinic and is going to school full-time for an education degree.

But her biggest stressor is worrying about health insurance.

Cruz, 47, of Pharr, Texas, makes about $30,000 a year and cannot afford the insurance offered by the pain management office where she works.

Her oldest daughters, college students, also have no insurance. Her youngest daughter, Korrie Cantu, is 17, young enough to receive coverage through the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, a federal program for low-income families who make too much to qualify for Medicaid.

But even that is not guaranteed: Last year, as Cruz was preparing to apply for CHIP renewal, Korrie’s coverage was suddenly yanked for more than a month.

“I was walking on eggshells,” Cruz said. “Even driving, because you always think, ‘Oh, what if I get into a car accident?’ Or Korrie would say, ‘I’m going to go ice skating,’ and I would think, ‘No, that’s not a good idea.’”

Raquel Cruz, bottom left, with her daughters Kellie Cantu, 23; Korrie Cantu, 17; and Kerrie Cantu, 19. Cruz and her two oldest daughters do not have health insurance; her youngest is covered by CHIP, but briefly lost insurance last year.Courtesy of Raquel Cruz

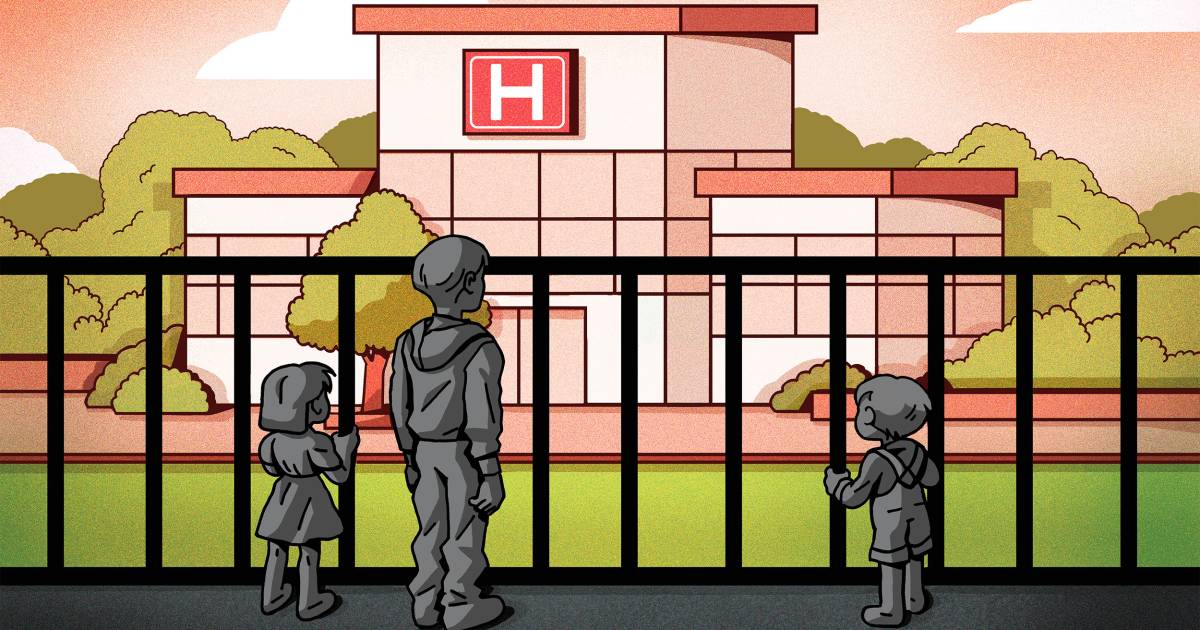

Korrie is far from the only child who lost insurance in 2017, and not all were fortunate enough to get it back like she eventually did. Last year, the number of U.S. children without health insurance jumped by 276,000 — to 3.9 million, up from a low of 3.6 million in 2016 — according to a report published last week by Georgetown University.

It was the first increase in the number of uninsured children in America since 2008, when Joan Alker, the executive director of Georgetown’s Center for Children and Families and lead author of the study, started keeping track of the data.

“What was really disturbing was that the number went up even though the economy is doing so well. We would expect the number to go down,” Alker said. “Kids are falling off.”

“What was really disturbing was that the number went up even though the economy is doing so well. We would expect the number to go down.”

Alker said employer-sponsored health insurance coverage went up last year, an expected result of a good economy. Yet losses in public insurance coverage, including CHIP, Medicaid and direct coverage through the Affordable Care Act marketplace, declined enough to push the overall number of uninsured children up.

Multiple factors led to that: states refusing to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, creating a gap in affordable coverage options for low-income families; federal budget cuts to outreach programs for the Affordable Care Act; and federal policies targeting immigrants that discourage people from other countries, even if they are legal U.S. citizens, from signing up for federal health insurance.

The government’s delay over renewing funding for CHIP, with some families not reapplying because they were uncertain whether the program had run out of money, also contributed to the chaos, experts say.

Cruz believes the blip in Korrie’s coverage was due to an administrative misunderstanding on the government’s part regarding her renewal application and does not know if it was connected to Congress’ failure to meet a September deadline to allocate funding for the program.

University of Chicago medical students host rally to call on Congress to reauthorize funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in Chicago on December 14, 2017.Scott Olson / Getty Images file

She still worries it could happen again and is not sure what she will do once Korrie ages out of the program next year.

“If you don’t have insurance, what if something happens?” Cruz said. “I would still take her to the emergency room, but I know it’s going to be out of pocket.”

Swapna Reddy, a clinical assistant professor at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions, called the drop in coverage rates “heartbreaking” but not surprising, given the Trump administration’s unwillingness to embrace former President Obama’s signature health care act.

“While Congress was not able to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act last summer, what we have seen is these incremental deaths to it by a million paper cuts,” Reddy said, citing reductions of up to 90 percent in government funding for health care “navigators,” people who help customers enroll in and renew federal health insurance plans. In addition, there was a drastic cutback in the amount of advertising for federal marketplace health plans that the government paid for last year.

People protesting proposed cuts to Medicaid are removed outside Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s office on June 22, 2017.Jacquelyn Martin / AP

Even health care decisions not directly aimed at coverage for children often had unintended consequences — such as in states that did not expand Medicaid coverage. Three-quarters of the children who lost coverage in 2017 live in such states, and uninsured rates for children increased at almost triple the rate in nonexpansion states, according to the Georgetown report.

Reddy said this is consistent with decades of data on Medicaid.

“When Mom and Dad are insured, you’re more likely for the whole family to be insured,” she said.

But even some families who are not considered low income made the difficult choice to forgo insurance last year due to ballooning costs.

“If something catastrophic happens, we’re screwed.”

Whitney Whitman, 43, of Bird Creek, Alaska, works as a professional counselor and mediator; her husband is a plumber. Neither is offered health insurance through work and they make too much for any public assistance to cover their 8-year-old daughter and 11-year-old son. Still, they do not make enough to feel justified in spending thousands of dollars a year to insure their family.

Whitney and Jason Whitman pay out of pocket for annual checkups for their children, Oona, 8, and Odin, 11, because they cannot afford insurance.Courtesy of Whitney Whitman

“Luckily, we are very healthy people. We have no major need,” Whitman said. “But if something catastrophic happens, we’re screwed.”

Whitman pays out of pocket for annual checkups for her children and herself, and for dental care for the kids. If a major health problem crops up, her plan is to use a nearby faith-based nonprofit hospital that will take them in, regardless of insurance status.

“I don’t prevent my kids from doing anything, but I live in fear,” she said. “I live in fear at every soccer game. They have a program at their school where they go to the local ski resort and go downhill skiing for six weeks. For those six weeks, I’m like, ‘OK, let’s just hope.’”

Like Alaska, Texas, where Cruz and her daughters live, was one of 12 states that last year had rates of uninsured children that were higher than the national average.

In Texas, 10.7 percent of children are uninsured — the highest rate in the country. One in five uninsured children in the U.S. lives in the state.

The problems in Texas are numerous. Experts say in addition to being a Medicaid nonexpansion state, it has a high rate of immigrants, and certain Trump administration policies most likely deterred legal immigrants from seeking health insurance. One such policy was the “public charge” rule, a proposal that would allow officials to consider applicants’ past use of government services such as Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) when deciding eligibility for green cards or legal entry to the U.S.

That meant immigrant parents with children who are U.S. citizens shied away from seeking insurance their kids are entitled to, Alker said.

“The Trump administration is leading those families to be worried about interacting with the government,” she said, adding that their fears are likely to grow, further pulling down the rate of insured children.

Cruz, who was born in the U.S., does not have to worry about immigration policies affecting her family. But she is constantly looking for ways to make the most of her paycheck for fear that she will need money for an unexpected health issue: She does not have cable television or internet, frequently turns lights off in her home to cut down on her electric bill, and never eats out.

She looked into paying for insurance through her work for next year, but even the cheapest option was above her budget. Family plans through the Affordable Care Act did not feel feasible either, and she said she would have felt guilty insuring only herself.

“Honestly, as a mother, I cannot get insurance for myself and not get insurance for my girls. I would feel bad,” she said.

While the decline in children’s insurance rates nationwide may persist, Alker said there are ways to ease or reverse it.

“A single surefire way to turn this around would be expanding Medicaid for states that haven’t,” she said. “Besides that, I think we need a rededicated national effort to get this number moving in the right direction.”

“This has been a source of enormous progress that has had bipartisan support in recent years,” she added. “We need to make this a priority again.”

Be the first to comment